Some people master another language for travel, work, relationships, education, networking and culture; others even go to the effort of learning fictional languages from their favourite books, movies and TV shows. But it is not often that people turn to ancient linguistics in search of discovering new forms of communication.

|

| Spanish lecturer teaching two students Images by Jay Grabiec, East Illinois University. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/2auDKkG |

Well, to learn any language

requires a certain amount of passion and discipline. It also requires a

community and environment where people can practice and converse using

day-to-day vernacular. Having a platform in place is imperative for the

preservation of any language, especially as future opportunities to use Old

English in a Kentish alehouse or at a Mercian market are unrealistic,

unfortunately.

|

| Anglo-Saxon tradesman Image by Amhjp Photography. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/noTp1L |

Language has always been a

popular subject and past-time for students and hobbyists around the world. For

budding linguists who use English as their mother-tongue, a recurring question

tends to be: "What language is the easiest to learn for native English

speakers?" Well, though it is not widely spoken, Frisian (or West Frisian)

is the most straightforward to learn. Another rival contender for this title is

Norwegian. Here are some quick demonstrations of Frisian and Norweigan:

(Frisian) Myn namme is...

(Norweigan) Mitt navn er...

If you haven't already

deciphered, both phrases mean 'My name is...' (the Frisian version is a big

giveaway!). Like English, Frisian and Norweigan are Germanic in origin;

however, English and Frisian are categorised as West Germanic, whereas

Norweigan is North Germanic. To understand the diachrony of how they became to

be so similar, we must go back to the formative years of English history.

Approximately in AD 450, Germanic tribes invaded Britain from Northern Germany,

Southern Scandinavia and Friesland (modern-day Netherlands). These tribes,

which later amalgamated into the Anglo-Saxon people, would conquer and expel

the native Celtic Britons (or, as they are also known: Romano-Britons). Thus, Germanic

dialects spoken by the now Anglo-Saxon ruling elite would replace the native

Brittonic (or Brythonic) language. The Brittonic influence on Old English is

still a debate which causes a fervent divide between historians and

philologians. The linguistic impact of the Britons is widely considered to be

too speculative and minor to have had a profound effect on Old English

etymology, toponymy and grammatical structure.

|

| Anglo-Saxon Reenactment Battle Image by Amhjp Photography. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/nFo4qM |

As the Anglo-Saxons settled

Britain, they would create separate kingdoms—most notably East Anglia, Essex

(East Saxons), Kent, Northumbria, Mercia, Sussex (South Saxons) and Wessex

(West Saxons). Old English would flourish in the form of dialects within these

kingdoms (i.e. Kentish, Northumbrian, Mercian and West Saxon). Old English is a

synthetic language like German, Greek and Russian. Synthetic languages use

grammatical inflexions and agglutinations to categorise and morph word tenses,

moods, persons, numbers, cases, and genders. Consequently, due to the Germanic

core of Old English, a present-day English speaker would likely have a hard

time trying to communicate with a pre-12th-century Anglo-Saxon. In contrast, a

present-day German speaker would be able to recognise some similarities in

phonetics and lexical flow. Here are some examples of Old English grammar using

the noun Rodor,

which translates as sky or heavens.

~beorht (bright,

clear-sighted, clear-sounded, magnificent) - Rodorbeorht (heavenly, bright).

~cyning (king) -

Rodorcyning (king of heaven, Christ).

~lihting (shining,

illumination, light) - Rodorlihting - (dawn).

~stōl (stool,

chair, throne) - Rodorstōl (celestial throne).

~torht (bright,

beautiful, illustrious) - Rodortorht (heavenly bright).

~tungol (heavenly

body, star, constellation) - Rodortungol (star of heaven).

|

| Escomb Anglo-Saxon Church Image by David Pollard. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/271N8mG |

The propagation of Christianity would then sweep the Anglo-Saxon world at the beginning of the 7th century. This new religion would bring its Latin scripture replacing the Germanic Runic alphabet. Naturally, some words were exsorbed into Old English:

Altaris (Latin)

- Altar (Old

English and Modern English)

Apostolo (Latin)

- Apostel (Old

English) - Apostle (Modern English)

Missa (Latin)

- Messe (Old

English) - Mass (Modern English)

Monachus (Latin) - Munuc (Old English) - Monk (Modern English)

|

| Viking Warriors Marching Image by Ian Livesey. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/2gGLMPF |

The Viking invasion of England during the 9th century brought about further changes and near extinction to Old English. During this period, Anglo-Saxon England was made up of four dominant kingdoms: East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria and Wessex. Three of these dominions had fallen victim to the Danish and Norse occupation; only Wessex still stood firm. In 878 at the Battle of Edington, history would be made on a knife-edge as Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, would make his last stand and obtain victory against the Vikings. Alfred's success at Edington would help to secure the survival of England's future and its language. It also turned the West Saxon dialect into the main form of Old English.

|

| Two Anglo-Saxon Women Sewing Image by Anthony D Barraclough. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/2jwBv1d |

The Scandinavian influence didn't end there, after the Battle of Edington the country was diagonally split in two. The Anglo-Saxons would take the South and South West, and the Danish Vikings would take the North and North East—a region which would be known as the Danelaw. Alfred implicated a treaty that would not allow Danes or West Saxons to cross the border unless for trade. During this time of peace and commerce, the Viking tongue called Old Norse/Old Danish would intermingle with Old English leaving an indelible imprint. Some examples of evolving cognates:

Deyja (Old Norse)

- Dīeġan (Old

English) - Die (Modern English)

Grænn (Old Norse)

- Grene (Old

English) - Green (Modern English)

Jarl (Old Norse)

- Eorl (Old

English) - Earl (Modern English)

Knífr (Old Norse)

- Cnīf (Old

English) - Knife (Modern English)

Plógr (Old Norse)

- Plōh (Old

English) - Plough (Modern English), although, the Old English form refers to a

size of land used for ploughing.

Rót (Old Norse)

- Rōt (Old

English) - Root (Modern English)

Taka (Old Norse)

- Tacan (Old

English) - Take (Modern English)

|

| Norman Knights Image by pg tips2. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/NgYEWp |

The Norman conquest of

England during the 11th century brought a further influx of Latinate words from

French, resulting in Old English starting to evolve into Middle English. Middle

English was a type of dialect which was widely spoken until the late 1400s, and

it combined Old English cognates with Romance influences from French and Latin.

It was relatively more coherent for a Modern English speaker in terms of

spelling and grammar, but still shared some vowel pronunciations similar to Old

English:

Segen (Old English)

- Seyde (Middle

English) - Said (Modern English)

Ne (Old English)

- Nat (Middle

English) - Not (Modern English)

Fram (Old English)

- Fro (Middle

English) - From (Modern English)

Genóh (Old English)

- Ynogh (Middle

English) - Enough (Modern English)

|

| Select Homilies of Ælfric by Henry Sweet 1885. Private collection |

Between the 15th and 18th century Middle English would develop into early Modern English. The outcome of this change would create the Great Vowel Shift, which significantly altered the pronunciation of words. The jump from Old English to Modern English would make the vocabulary rise from roughly 50,000 to 170,000. Moreover, it developed a much simpler syntax structure. It went from being a synthetic language that was predominately Germanic, to an analytical language with added Romance vocabulary; hence why English has a Germanic-Latinate mix which is both weird and wonderful!

So, is Old English a dead

language? Yes and no. Many of its words still exist but in a different

form:

Old English: Blōd

Modern English: Blood

Old English: Consul

Modern English: Consul

Old English: Flyht

Modern English: Flight

Old English: Hunta

Modern English: Hunter

Old English: Panne

Modern English: Pan

Old English: Wæter

Modern English: Water

A fair comparison can be made

with Classical Latin, as it shares similar circumstances. Both Latin and Old

English never really died, they respectfully evolved into the modern Romance

languages (Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian and Romanian) and Modern

English. There are educational courses available to study both subjects, but

status similarities differ when you consider the use of Latin is habitual for

100 fluent speakers. Sadly, Old English does not share this status.

|

| Latin Wall Writing Image by Stephen Shankland. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/nrDKdJ |

There are three key points as

to why the Anglo-Saxon language is worth learning:

- Maintaining its survival: Some

contemporaries today might see it as being unfashionable or irrelevant,

but this outlook could be different for future generations. Solely keeping

Old English in the confines of books and lecture rooms does not guarantee

its preservation; nor does it broadly attract potential learners. If a

language is to survive, it must first thrive in some capacity.

- Expanding historical knowledge: The people of the

past have left an imprint on the world through their everyday speech.

Researching Old English can not only assist us in understanding

Anglo-Saxon idiosyncrasies 1000 years ago, but it can also provide us with

an insight into the present synchronic form and future direction of Modern

English. Reading ancient texts—as it was initially intended to be

written—can supply new historical interpretations of historical figures

and events.

- Improving language proficiency: Studying Old English

does not only help to comprehend the roots of Modern English, but it can

also build the foundations needed for acquiring and understanding other

languages and cultures. When you learn a new language, you obtain a new

way of thinking which can enhance your communication methods. Such methods

of acquisition can open doors to learning additional styles of conversing,

especially when studying another Germanic language. "Eall on muðe þæt on mode" is

an apt Anglo-Saxon proverb which translates as: "All in the mouth that's in the mind".

|

Stained Glass Window of Alfred the Great https://flic.kr/p/6iXbxK |

"Remember what punishments befell us in this world when we

ourselves did not cherish learning nor transmit it to other men."

~ King Alfred the Great

Alfred's foreboding quote referred to the sackings inflected by Viking raids on monasteries like Iona, Lindisfarne and Monkwearmouth–Jarrow. As a result of these incursions, the Vikings would slay many learned clergies while burning libraries and purloining artefacts. Clerical residents would oversee places of religious worship which were held as hubs for knowledge and learning. In Europe during the medieval period, Latin was the universal language for religion, law, academia, governance and literature; but, it was not a vernacular the ordinary people understood. The type of Anglo-Saxons who were primarily literate in Latin tended to be high ranking members of the Church and realm. With the former starting to dwindle in numbers due to Viking attacks, Latin documents of governance and education were unable to be proficiently translated. This outcome risked the mistranslation and disregard of sacred oaths and laws relating to religion or state.

|

| Lindisfarne Priory with Lindisfarne Castle in the distance Image by Daniel Letford. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/2jRofmG |

|

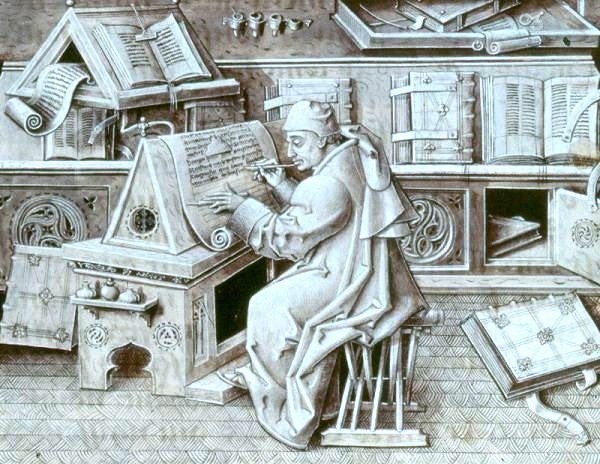

| Medieval Scribe Image by Lamson Library. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/6Ujo4P |

Thanks to the efforts of Alfred the Great, Old English would be one of the first native languages in Europe to have notable scriptures translated from Latin. By advocating the production of these translations, Alfred was creating a text which was no longer exclusive to clerical intellectuals and other privileged members of society. He believed in bettering the living standards of his people by providing them with the freedom of knowledge. As a devout Christian, Alfred felt that morality and enlightenment could only prevail through education. Even today, we collectively try to celebrate and preserve these esteemed ideals.

"No language is justly studied merely as an aid to other

purposes. It will in fact better serve other purposes, philological or

historical, when it is studied for love, for itself."

~ J.R.R. Tolkien

|

| Beowulf book cover Image by Unwieldy Locutions. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/37bzUe |

Though Tolkien was a

respected professor and philologian at Oxford University, he is better known

for being the author of The

Hobbit and The

Lord of the Rings trilogy. As an expert of Old English

literature, he appreciated its poetical beauty, and would notably be inspired

by such works as Beowulf when

writing his renowned books. Because of these influences, Tolkien's creative

works revolutionised the fantasy genre for many avid readers and budding

writers for generations. As well as making a universal impact on the literary

sphere, Old English has acted as a progenitor for the most widely spoken

language in the world. The widespread use of English has undeniably shaped

modern western civilisation and global pop culture, and it has been a journey

which all started with its Anglo-Saxon forebear.

|

| English Language Centre Image by University of Victoria. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/9htstE |

|

| Road Sign in English and Welsh Image by johnsti777. Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/2js1mK4 |

We only to have to look to our Celtic neighbours to see the cultural benefits gained from revived languages like Breton, Cornish, Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh. Many of these languages had previously been small unofficial dialects or had become nearly extinct through low status. Now, Celtic linguistics is making a resurgence and bringing communities closer together through local governance, education, business and the arts. Although commendable, it is not essential to teach Old English in schools, nor is it necessary to have it written across signs and billboards. Nonetheless, it would be a great shame to overlook something which has contributed so much to our history and culture. Old English does not solely belong to the Anglo-Saxons; it belongs to all English speakers of today and tomorrow onwards.

Author: Thomas Davies

Refs/Sources:

N. Parsons, David. Sabrina in the thorns: place-names as

evidence for British and Latin in Roman Britain. Transactions

of the Royal Philological Society.

Coates, Richard, "Invisible

Britons: The View from Linguistics", in Britons in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Nick

Higham, Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies.

https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/easiest-languages-for-english-speakers-to-learn

de Vaan, Michiel. Etymological Dictionary of Latin and

the other Italic Language. Brill Publishing.

https://web.archive.org/web/20110501100652/http://www6.ocn.ne.jp/~wil/

Abels, Richard. Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and

Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Longman Press.

Attenborough, F.L. The laws of the earliest English kings.

Cambridge University Press.

Lavelle, Ryan. Alfred's Wars: Sources and

Interpretations of Anglo-Saxon Warfare in the Viking Age.

Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydel Press.

Parker, Joanne. England's Darling.

Manchester: Manchester University Press.

https://aclerkofoxford.blogspot.com/p/old-english-wisdom.html

http://www.heimskringla.no/wiki/Main_Page

https://web.archive.org/web/20100407164322/http://www.omniglot.com/writing/oldenglish.htm

Watts, Richard J. Language Myths and the History of

English. Oxford University Press.

Robinson, Orrin. Old English and Its Closest Relatives:

A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages. Stanford University

Press.

Hogg, Richard M.

"Chapter7: English in Britain". In Denison, David; Hogg, Richard

M: A History of the

English language. Cambridge University Press.

Potter, Simeon. Our Language.

Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin.

Middle English–an overview - Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford

English Dictionary.

Fisher, Ellen Rose. An analysis of Tolkien's use of Old English language to create the personal names of key characters in The Lord of the Rings and the significance of these linguistic choices in regards to character development and the discussion of humanity in the novel more widely. School of English, University of Nottingham.

No comments:

Post a Comment